A short breakdown of Compressed Air Batteries

# Compressed Air Batteries Recently I once again stumbled over some of the problems that grids, consisting mostly of renewable energy, pose. Almost all these problems, however, could be resolved by implementing various types of energy storage. And a lot is being done here already!

# Compressed Air Batteries Recently I once again stumbled over some of the problems that grids, consisting mostly of renewable energy, pose. Almost all these problems, however, could be resolved by implementing various types of energy storage. And a lot is being done here already!

In Germany, for example, 24 GWh of battery capacity was installed in 2025. This would be enough to provide electricity to roughly 100,000 households for one month, or power Oberriexingen for 4 years.

However, this calculation disregards one thing: battery storage is not well suited for storing energy over a long period of time. There are multiple reasons for this, but the most prominent are:

- Batteries need to cycle frequently to amortise and become cost effective

- Batteries permanently lose capacity over their lifetime due to aging even if they are not cycling frequently, which vastly increases cost

- Batteries self-discharge over time, meaning that batteries lose stored energy over time

And other frequently named technologies for storing energy, such as capacitors, have similar problems.

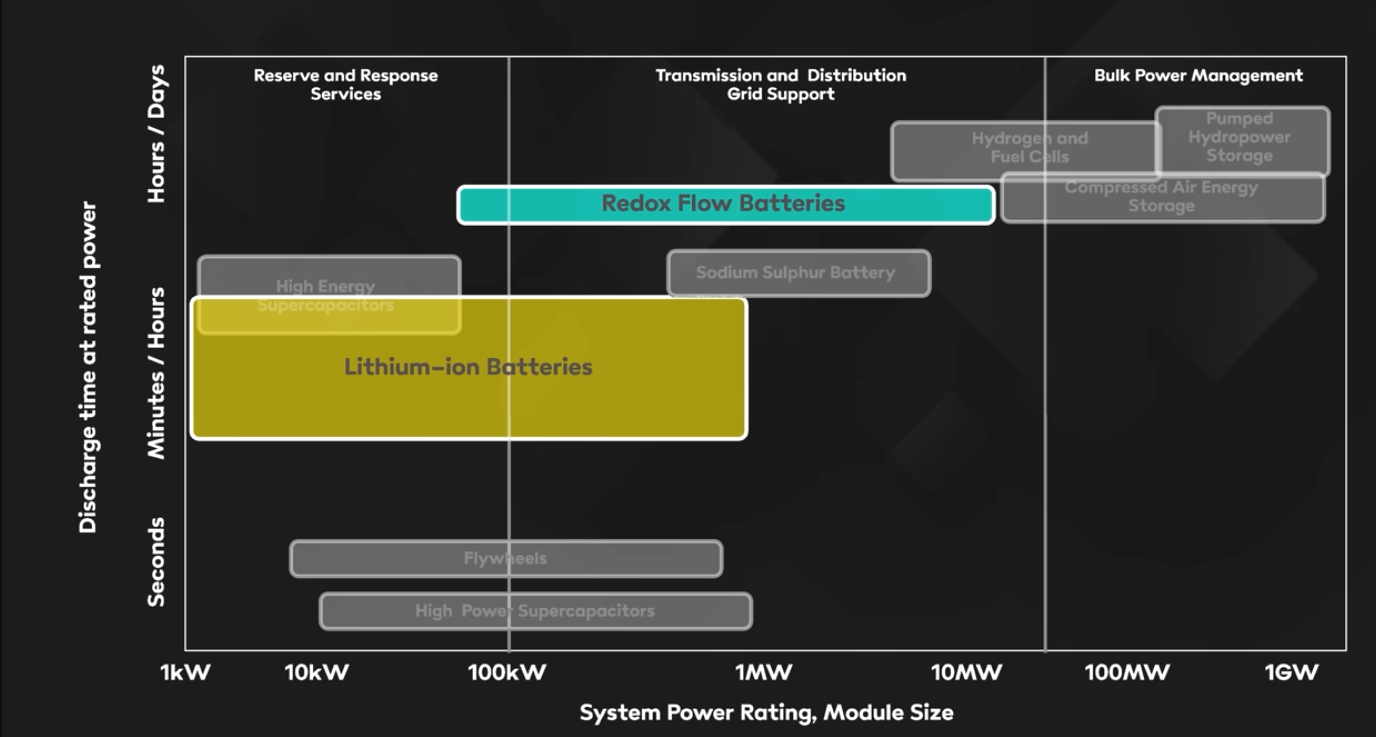

That’s why it is essential to also implement long term energy storage such as pumped hydro, power-to-gas or compressed air energy storage (CAES). The latter of these has recently made some headlines, as advancements in CAES seem to make it a viable option for green energy storage.

CAES has been around for a while, with the first plant ever built in Germany in 1978. However, even though in theory it is one of the cheapest means of storing energy, especially at big scale, CAES has never been able to reach this potential. The main reason for this is good old thermodynamics.

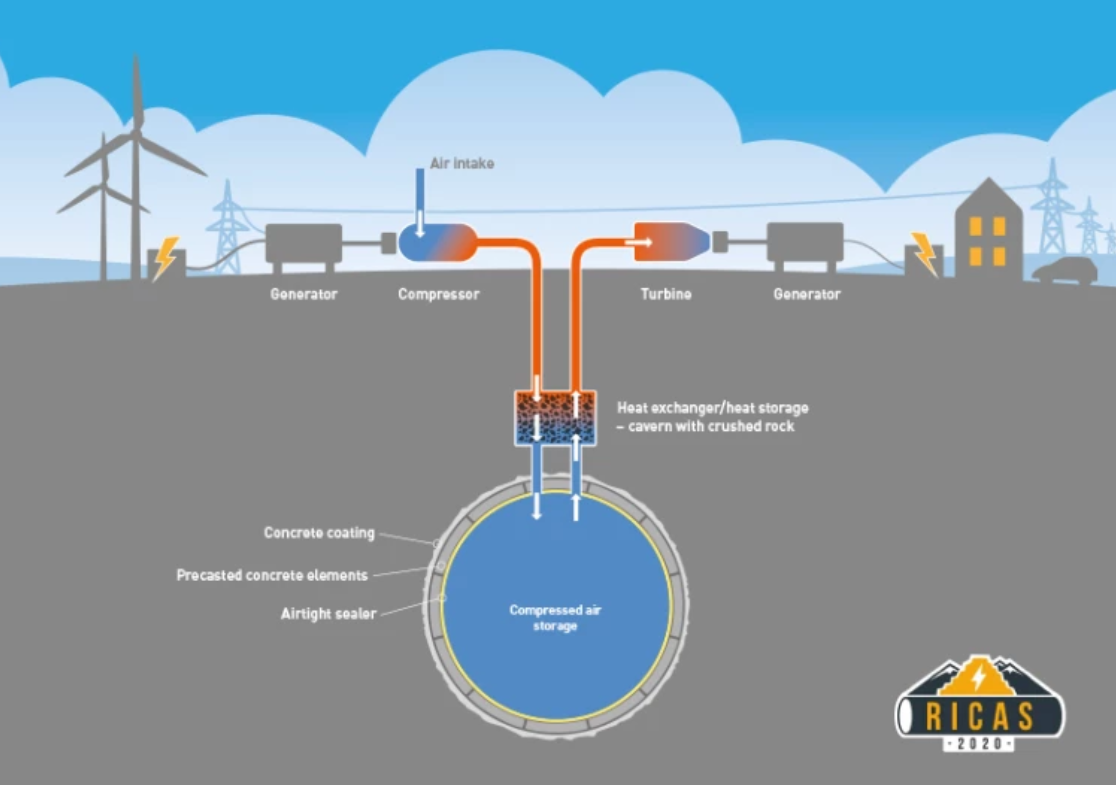

CAES stores electricity by compressing air into a high-pressure tank or cavern. When power is needed, the air is released and expanded through an expander or turbine to drive a generator. In theory, this process seems very simple, as it is the same concept used by gas turbines. However, the one caveat here is that as the gas is released from the pressure tank it cools down (ideal gas law), which not only majorly decreases the efficiency of the turbine, but could also damage the turbine by freezing it.

In existing CAES plants, this issue has typically been addressed by reheating the expanding air with fossil fuels, thereby reducing the overall efficiency and undermining the technology’s potential as a truly zero emission storage option.

This dependency on fossil fuels, however, is now being challenged by new technologies using adiabatic CAES, where the heat released during compression is stored and reused later during expansion. Storing heat and distributing it within a system is not an easy task, but a company called Hydrostor seems to have made major progress.

They have built an adiabatic CAES plant in Australia that came online in 2025, and they claim a round trip efficiency of 65% with zero emissions. Another project they started building this year in the USA is even supposed to reach efficiencies of up to 75%.

But Hydrostor is not the only company investing in this technology. In Europe, Corre Energy and Siemens Energy have partnered to build plants in Germany and the Netherlands, respectively. In China, the first commercial adiabatic CAES plants were connected to the grid in 2024.

This shows the momentum that CAES has picked up over the last few years. The next few years will decide whether it will just be another promising technology that cannot live up to the hype, or if it will play a big part in the future of our energy grids.